Around The Corner

Basketball and being anywhere together

Once upon a time I could summon my homies all the way to Frankford with an incredibly lurid promise: I knew where we could get the best runs, right around the corner from my house. We were in high school, and on a daily basis we’d all gotten a teaser toward real pleasure at the gym, or during lunch, or cutting some class and running a few games of full court at peak intensity (till coach Taylor strolled out of his office with that damn whistle like, what the fuck are y’all even doing in my gym?). Ervin, Tasia, and Clarence—the latter who kept calling Frankford “the gutter” even though he was from North Philly—would come over from Mastbaum. Jonathan would meet us from wherever, because not only were niggas really running up where I’d said they were, they also had new nets and fresh paint on the court; sometimes even glass backboards and breakaway rims. Of course I was talking about Mayfair, that corridor between Frankford and the greater northeast.

“Nigga this ain’t round no dang corner,” Ervin would say, a half hour into our walk.

But it felt around the corner, how I remembered it, how the situation meant something for its lack of production and the way it stretched out leisure time till we all learned to love it.

We already had Whitehall nearby, with its notorious bucket rims, but from the now burned down 5120 Glencloch where I used to live, you could, with nothing but your own two to ten feet, hit up Wissanoming or Moss, Devreaux or Roosevelt, Vogt or—if y’all were feeling really spicy—Russo just past Cottman on Torresdale where Terrell lived. Now, did all white boys enjoy the encroachment upon said territory as it bled and bled into a more, how to say this… multicultural affair? Absolutely not. But did it teach you who the real ones were, and who was not? Most definitely.

If we showed up two, three, four of us at a time to Moss, with Gatorades and dollar hoagies, we might fill out the half court of strangers playing three-on-three; we were just what they needed, and they were exactly what we were looking for. From such a point forward, we’d know each other at least a little beyond the terms of pigment: whose daddy worked where, whose uncle and them were on crack or pills or, who had suffered the greatest loss. “Contact” is what Samuel R. Delany calls such moments, from Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities, those vital contexts where people of different classes collide, those damn near extinct punctums toward the promise of a social life.

But this could all be misleading though, about Philadelphia, which I’ll describe as a city of neighborhoods. We are not New York or L.A., Miami or Atlanta, nor have we ever pretended to be. Hell, we hardly had public transportation or the money for it, let alone forward reflections on the latest SEPTA budget cuts. These hikes we took were more along the outskirts of anything like a city, which was already then, and for us dedicated mostly to, transport to and from some form of service work.

Outside of basketball, connections were primarily through such work, or the high school you went to, maybe whose sister or friend you were too shyly crushing on. On the court though, you’d meet Bob Muscrove from Northeast High with the handle; Carlos with the fine older cousin in college who we all hoped would drive him to the park, and stay to watch (always, where ya cousin and her friends at?); or Lorenzo from Swenson that half of us, upon seeing him play for the first time, swore up and down was going to the NBA. Over time, if any of the aforementioned characters were not at a given court where runs could be had, we’d just send out the bat signal and poof—twenty minutes later you’d have a whole extra squad waiting on the bench arguing over who got next. But you had to be careful, of course, because a quick jaunt out to play a game or two could turn into an all night affair where thirty or so mismatched characters of questionable origin would end up walking another half hour to the next court with the best lighting after dark, too many hours after y’all should have been home.

And even if you ended up two hours away, that was around the corner too. It had less to do with actual proximity, and more to do with the feeling of being surrounded by others who were not you and who, through tacit agreement, would do no harm to the shared institution. Yet just as important, nobody would forget when you got dunked on, or let you lie on your game, and if you sprained your ankle (again) no one would let you limp home alone. A fondest of memories I can’t help but recall was Erv and Clarence carrying me home from Roosevelt all the way to Glenloch Street without a second thought after I tore the ligaments in my right ankle, which we all understood, I think, as a sort of permanent ending.

There’s precious little “we” walking anywhere at this point in my life, with everybody working overtime or three more jobs. Still, I sometimes dunk on the youth out front of my house who can’t imagine my real name and have dubbed me so-and-so’s dad, or inaugurated me into the more classical nomenclature “old head.” But it remains true that in the aftermath of this era, whenever somebody’s “buy here pay here” Nissan Maxima broke down, you could call another somebody from around the corner to help you fix it. When my bank account (overdrawn by umpteen dollars) has seen better days, I’ve called somebody from around the corner who never hesitated to help me get right, nor did they feel the need to wallow in shame for half a lifetime when asking me in return. Sometimes I wished these niggas would not need help moving, but there we all were, old ass backs lifting the overwrought sectional somebody bought on credit because they swore they wanted to be cute. And with no walk to whine about they’d be like, “Why you got all these motherfuckin books!?” as people swear up and down they’ll never help me move again. But they always did.

To this very day, what I think separates one mode of desperation from those further down in my own asocial past is simple. Should any of us fall yet again on hard times, let’s say you had the unspeakable occur at home or you were out on your ass entirely, we could, and would, beyond the pieties of comfort or protecting one’s peace, commandeer a couch or transform space into place in that holy grail of squatting locales—the finished basement—without a drop of shame, and help you make it around the corner.

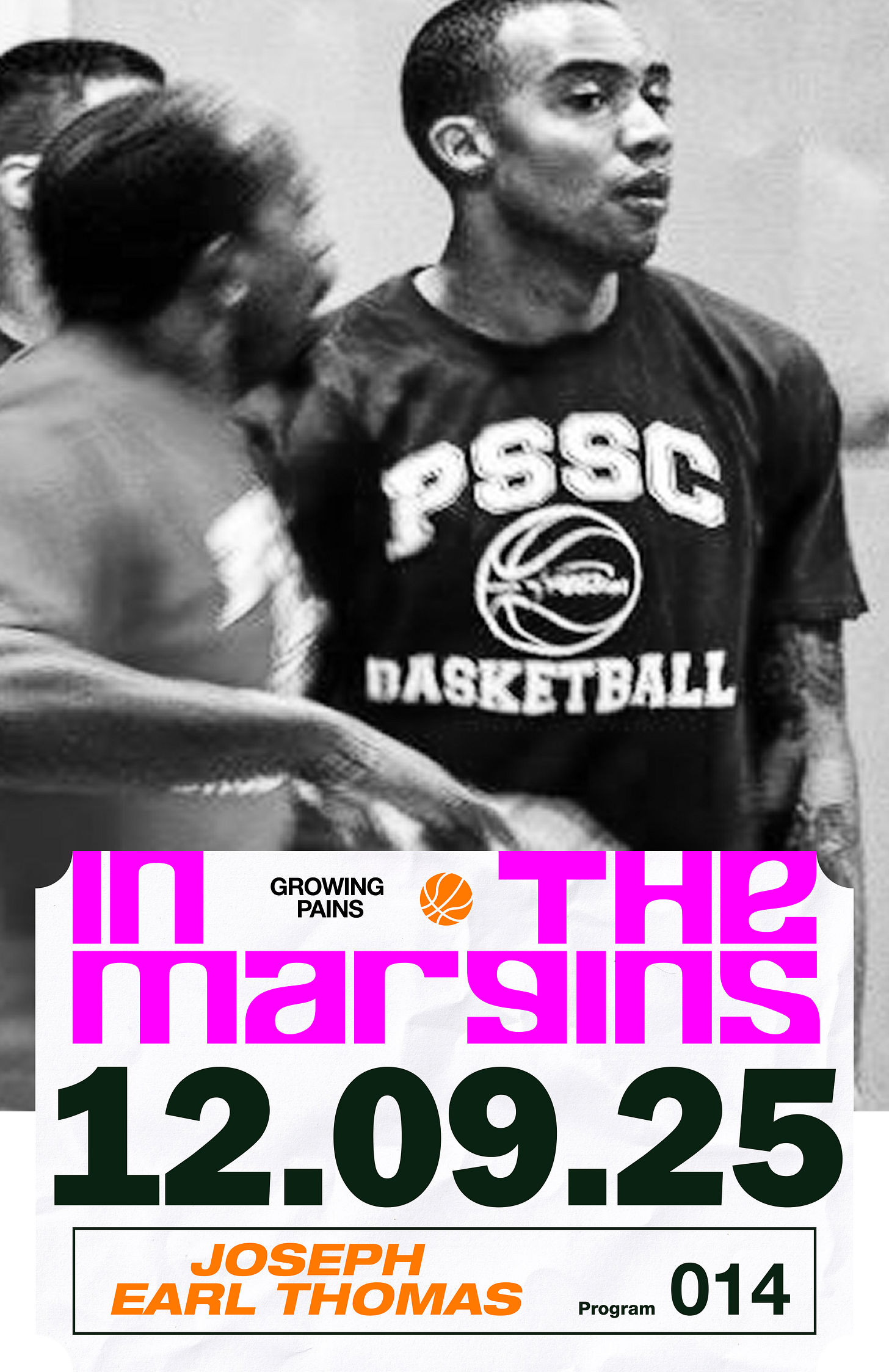

Joseph Earl Thomas is a writer from Frankford, Philadelphia.