Before the WNBA, there was Ft. Shaw

On the first women’s basketball championship game

The game started at 4:00pm in the afternoon on a chilly, cloudy early October day in St. Louis. It was the second game in a best-of-three series, but it had been over a month since the players had faced each other. The all-white St. Louis All-Stars team, who had lost their first match, had taken an extra month to practice so that they might stand a chance of beating their opponents, the Fort Shaw Indian School Girls. The two team captains — Belle Johnson and Flo Messing — met at center court and shook hands.

It was 1904, thirty-two years before basketball would be an official men’s sport in the Olympics, seventy-two before it would be an official women’s sport, and almost a hundred before the founding of the WNBA. This game, played as part of the St. Louis World’s Fair, was the first national (or international) championship women’s basketball game ever played.

The second modern Olympics were running simultaneously with the World’s Fair, using many of the same buildings, and drawing from the same fan base, and the October game was billed as “the championship of the world.” But it wasn’t only a competition of basketball skills, it was also a competition of race. The Ft. Shaw Team — Native American teenagers who had been forced to leave their community to study at boarding schools — had been pitted against the white team from St. Louis to show the racial superiority of the white women on that team. It was widely assumed that the white team would triumph.

When the game started, the 1904 World’s Fair was all but over. The summer had brought nearly 20 million visitors, excited to experience thrilling inventions of the new century — ice cream, private automobiles, and X-Ray machines all made their first public appearance at the fair — and learn about the people of the world. Over fifty foreign nations had pavilions, and nearly 1,400 indigenous people from across the United States were featured in what the fair organizers called “anthropology” exhibitions, where they were displayed and asked to demonstrate their “traditional” crafts, trades, dances, and music.

Alongside these exhibitions of primitivism, which scholars now call “human zoos,” 150 Native American students from boarding schools across the country were shown in a display of the federal government's attempt to “civilize” indigenous people across the country, including the girls on the Ft. Shaw team. They took public classes in reading, writing, and arithmetic; showed their skills as blacksmiths, sewers, and cooks; and spoke in English to passers-by. And they played sports. Belle Johnson and her teammates, high-school-aged girls who were far away from home, spent part of each day passing and shooting in exhibition games.

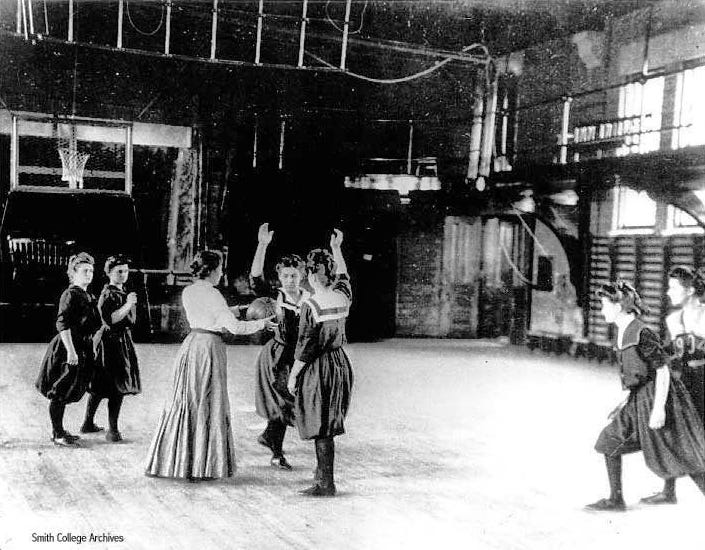

Basketball itself was barely more than a decade old. Invented in 1891 by James Naismith at a YMCA in Springfield, Massachusetts, it spread rapidly through YMCAs, schools, and colleges, and was seen as a truly “American” game. Women’s basketball began just a year later, when Senda Berenson adapted the rules for her students at Smith College, emphasizing passing, teamwork, and decorum over physical contact. Even with these more “ladylike” rules, the girls who first played basketball thrilled at the experience of competing and moving their bodies vigorously. Organized women’s sports were almost entirely new, and Berenson found that her students reported not only joy in movement, but increase in “endurance, lung capacity, alertness, courage, [and] toughness”. The women at Smith, and later throughout the country, found it intoxicating to excel physically in public. After centuries of being told to stay still, stay small, they were now running, moving, winning.

By the turn of the century, the sport had reached American Indian boarding schools through the same channels that had brought baseball and football (sports seen as part of the Americanization of Native American children). At Fort Shaw, in western Montana, basketball became popular thanks to the influence of Josephine Langley, a Blackfeet woman who had encountered the game at Carlisle (the infamous Indian Boarding School in Pennsylvania) and discovered that she loved the feeling of collaborating with a team, competing fiercely, and physically dominating. She brought it back to Ft. Shaw when she became the physical education instructor.

Langley and the girls at Ft. Shaw took to the game perhaps because it felt familiar. They had likely played and watched Double Ball and “kicking the ball” before coming to boarding school, which may have helped them develop teamwork and ball-handling skills they’d use on the basketball court. But also, they had spent their early girlhoods enjoying the freedom and joy of moving their bodies in nature, or finding “joyous relief in running loose in the open and roam[ing] over the hills,” as Dakota writer Gertrude Bonin put it in her essay collection in 1921. For the teenagers at Ft. Shaw physical movement had been a hallmark of their girlhoods, a time when they were with their families and communities, and were encouraged to run, jump, and roam. Participating and excelling at basketball was one of the only ways they could express that girlhood part of themselves.

Over a decade, the team grew and thrived. They played at games across Montana and, by 1904, newspapers called them “champions of the West,” a title they earned after defeating top women’s teams from Butte, Helena, and Seattle. Hundreds of white spectators came not just to watch basketball, but to gawk at the Native girls on the court. Officials at Ft. Shaw staged the games as a racial spectacle: the team was made to recite Longfellow in traditional dress, then dribble and pass in their hand-sewn bloomers. The intent was contradictory. The displays were meant to show the “savage” nature of the Native youth and their “natural” athletic ability, while also showing that they were physically inferior to white players. It was this confused stew of excellence on the part of the girls, and racism on the part of the school, that landed the team in at the St. Louis World’s Fair. Federal Indian officials wanted the best possible showcase of “civilized” athletic achievement, and they found it in the team from Ft. Shaw.

And so, in May of 1904, the team boarded a train and traveled more than 1,500 miles east, passing through unfamiliar cities and farmland before arriving in the fair’s bustling grounds. For four months, they played almost daily. Some days they faced other women’s teams from the region; other days they took on pickup squads assembled from fair workers or soldiers stationed nearby. Between games they toured parts of the fair sampling new foods and visiting exhibits, but they also joined in the cultural demonstrations staged for visitors — beadwork, singing, or greeting dignitaries — toggling between the uniforms of basketball and the regalia chosen by fair organizers.

By the fall, they’d beaten almost every team they’d faced, and it was with this record of achievement that they went into the final games against the St. Louis All Stars. The first game of the series, held in early September, had gone to Fort Shaw in a decisive win. The Missouri Girls were tough, fast, and taller on average, but the Montanans’ relentless defense and tight passing wore them down. A month later, on that chilly October afternoon, the second game began much the same way — both teams crowding the ball, the pace quickening, the sound of skirts swishing as players pivoted and lunged.

Ft. Shaw’s strategy was simple: move the ball before the other team could set their defense, and force mistakes. By halftime, they had pulled ahead. Missouri fought back hard in the second half, their captain Flo Messing hitting long shots from the edge of the court, but Fort Shaw’s Belle Johnson and Nettie Wirth answered each basket. The crowd roared with every score, a mix of local supporters and fairgoers curious to see these “Indian girls” dominate a modern American sport.

When the final whistle blew, Fort Shaw had won again, sealing the series and the title of “World Champions.” The players posed for photographs in their pleated skirts and white blouses, the championship trophy at their feet.

After the game, federal officials held up the victory as proof that boarding schools could “civilize” Native youth. The newspapers that week marveled at their skill, with one reporter noting they had “played like veterans” and “beat their opponents at their own game.” For the rest of the fair’s final days, they were the main attraction at the Indian School exhibit, where they were also measured and examined as part of a eugenicist program of classification and study. The girls went home at the end of the Fair, graduated from Ft. Shaw, and became teachers and mothers spending the rest of their lives watching as the federal government further dismantled their way of life. “Darling Emma… Don’t forget the good times we had in St. Louie,” Genevieve Healy (one of the members of the Ft. Shaw team) wrote to her teammate Emma Sansaver. She describes the games in St. Louis as a highlight of her life.

The story of the Ft. Shaw team has all the beats of a perfect sports movie. An underdog team full of vivid characters overcomes tremendous odds to win a high-stakes title matchup, the first ever of its kind. And yet, few have ever heard of Genevieve Healy or Belle Johnson, or imagined what it might have been like to play on that cool October day in cumbersome bloomers. Like so much of women’s sports history, it is a story that has been largely forgotten.

But the legacy of the Ft. Shaw team isn’t only one of trailblazing. Although they were the first women’s basketball team to win a world championship and are the largely-forgotten predecessors of Caitlin Clark and Brittney Griner, the team teaches something much more fundamental about sport than merely being the first. Learning about the players and the coach, reading their descriptions of what it felt like to play together, to move their bodies, to win, is to encounter the essence of sport itself. At a time when so many factors were conspiring to constrain them — restrictive Victorian mores and clothes; racist ideas about Native American traditions; dominating notions of femininity that would keep them indoors and behind a stove — the girls on the team found a way to insist on a girlhood joy of “running loose,” as Gertrude Bonin put it. In basketball, they discovered the exhilaration of play, of movement, of teamwork. When everything in their world sought to control them, they carved out a space for girlish joy.

Sources for this essay include “Full Court Press” by Linda Peavy and Ursula Smith (2008) and “Wild Girls” by Tiya Miles (2024).

Image sources include: MontanaPBS and Zinn Education Project

Heather Radke is a writer and Contributing Editor at WNYC’s Radiolab. Her book, Butts: A Backstory, came out in 2022 and was selected as a best book of the year by Time, Amazon, Publishers Weekly, and others. Her essays have appeared in many publications, including The Paris Review, Longreads, and The Believer. She is currently working on a book about pre-adolescent girlhood.

A story I never knew about. Now I got to research these women to see if I can find info on their descendants. Great story.