EMPEROR SHOHEI

On bushido, Japanese emperor logic, and the great Shohei Ohtani.

It was something I immediately noticed. Upon returning for the first time in a decade to the neighborhood I spent my first years in. In Tokyo.

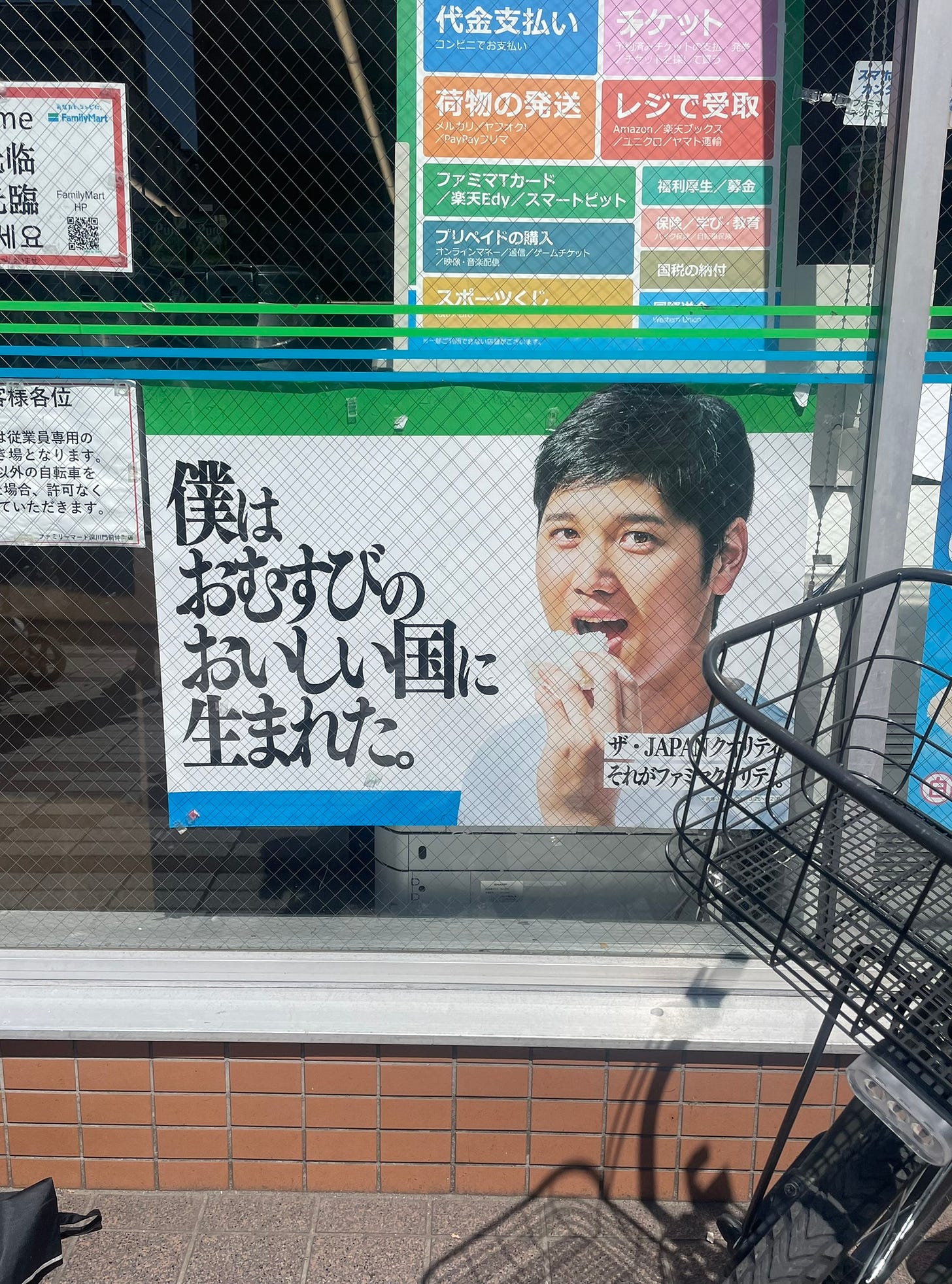

Shohei on every block:

Eating a snack on the front of every Lawson’s convenience store.

In a field of green tea leaves, holding a bottle of green tea, on the side of a bus stop.

On every vending machine, subway car, billboard. Advertising skin care, clothing, drinks. Every TV playing a seemingly 24/7 loop of Shohei highlights.

Part of the reason for this was that it was early April when I arrived, and we were a week into the Major League Baseball season. Shohei was the first player since baseball was black and white to attempt both pitching and hitting—and to excel at both, a feat thought impossible; who, at age 29, signed a ridiculous 10-year $700 million contract with the Dodgers, the largest ever at the time; and who’d follow this up with an MVP award and World Series victory his first season. He was the pride of Japanese baseball. And the Japanese love their baseball.

Even my mom, who could care less about baseball, speaks about Shohei with a moral reverence: “Did you know he deferred the majority of that $700 million, lowering his annual salary to about $2 million, so that the Dodgers could continue to sign players without exceeding the salary cap?” Even off the field, Shohei stands as an emblem of selflessness, team first, and unmaterialistic dedication to his craft that everyone can get behind (if blunted slightly by the knowledge that the money he’ll make from these ads draping Tokyo far exceeds even his highest-ever-to-date contract).

I mean, my man got $17 million stolen from him by his interpreter last year, and it took him months before he even noticed.

Shohei is making emperor money, and figures so prominently and unanimously in the Japanese psyche on Japanese storefronts and infrastructure. I can’t help but keep recursively thinking while walking around all month, “It’s like he’s a living emperor!”.

THE KOJIKI

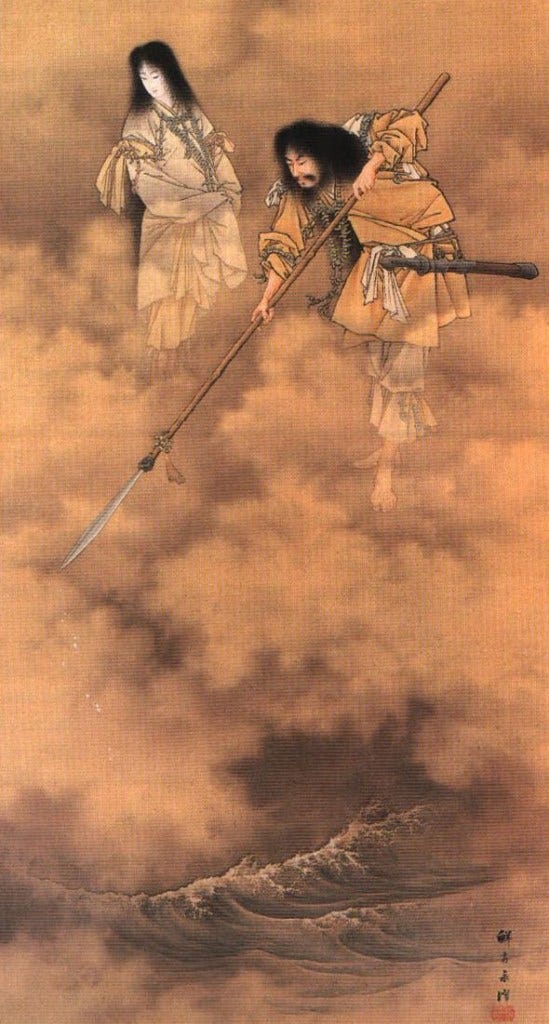

The Japanese creation myth, The Kojiki, was written in the early 700s. It’s not unlike the Western creation myth. It starts with an Adam and Eve corollary, Izanami and Izanagi. Izanami and Izanagi are “the male who invites” and “the female who invites,” in Basil Hall Chamberlain’s 1883 translation.

One has “too much of one part,” whereas the other has “not enough of one part,” so they put their parts together and make the islands and a baby.

Izanagi then makes the sun and moon out of his eyes, and the sea out of his nose.

And here we have the most crucial detail: Japan’s first Emperor, Emperor Jimmu, we learn descended directly from Ameratsu the sun god. His birth is mythically dated as February 11, 660 BC, which officially coincides with the birth of Japan.

Of course, this incorporation of the State Leader into the creation myth with a propagandist bent is a factor in many empires, from Ovid’s in Metamorphoses, to Virgil’s in The Aeneid, to for that matter Dante’s continuation of the Pax Romana Caesar worship into the early 1300s. One recalls the points in Ovid where he’s describing the first god of thunder and lightning, Jove, and quickly compares him to the current emperor, Caesar Augustus—“Just as your people’s loyal devotion is welcome to you, Augustus, so was his subjects’ to Jove…”

But to make your first emperor descend directly from the first god, and for this national mythology to persist as late as it did, is something different.

WORK IN JAPAN

I stayed at my uncle’s for some of my trip. Since I left Japan in 1994, at age 3, I’ve only been back three times—in 2005, 2015, and 2025. He’s never been to the States. Besides not seeming to have any particular desire to, the main obstacle is his work. He works as a tax man: he helps his clients, and never takes off work. He doesn’t seem to want to. He gets up at the same time every morning and comes back at the same time every night. He’s lived in this rhythm his entire adult life more or less, living in the same apartment.

Everyone in Japan seems to do their job with diligence and honor, no matter what it is. It’s something I noticed while walking around with my little sister that first week. On the walk from the Kasai station to my uncle’s, at a bigger intersection beneath the Tozai line, a crossing guard stands sentry beneath the freeway column like he’s about to go to war. Equipped with whistle, some type of baton, and a full-on outfit replete with lapels and patches.

Just doing his job so diligently and seriously.

“My man really takes this shit serious,” I say to my sister, with genuine awe.

My sister proposes that in Japan there’s a different relationship to social status and fame, which gets me wondering whether these things are connected: the Shohei worship, the serving of the divine Emperor, and the fidelity to one’s work. In Japan there’s less of a desire to climb some imaginary social ladder; instead, people are content to do the job they are assigned, and to do it well. With honor.

“It’s not like America where the leaders aren’t clearly defined, and anyone in a position of leadership is there arbitrarily, and everyone who isn’t in that position will be one day! Once the tables turn and they ‘make it’.”

Shohei is embraced because he represents everyone in the nation. When he wins, everyone wins.

HAGAKURE

This outlook of service to a lord being honorable and self-sacrifice for something larger not being anything to be insulted by, is of course connected to the thinking behind bushido: the way of the samurai and a line of thinking that ended in the Meiji period in 1868. The emperor is divine, and the lords are extensions of the emperor, and you serve your lord to the death. You will be remembered by how honorably you served your lord.

It’s obvious why this is a sketchy line of thinking. Hagakure, the book that lays out the samurai code, is seen by some as a celebration of the backwards thinking that led to the catastrophe of World War Two.

The self-sacrifice inherent in bushido, where you literally elevate the status of your lord, your leader to one who determines your life and death, it’s been argued, charts a direct line to the suicide bombings and military brutalism of the decades leading up to 1945.

And yet, others argue that it wasn’t the code of following a valid leader with bushido-like reverence, per se, that led to the catastrophe, but rather the fact of the military takeover of Japan by a handful of bloodthirsty tyrants. In their minds, the problem was that they were following the wrong leader.

In theory, bushido entails serving one’s lord with “honesty, justice, courtesy, courage, compassion, sincerity, honor, duty, loyalty, self-control”—virtues not unlike those preached by the Western incarnated man, directly descended from the first ever humans, in the West’s foundational myth (like Emperor Jimmu is in The Kojiki): Christ.

The difference being, Christ wasn’t said to be the first Political Leader of the Nation (at least not explicitly; it was essentially a slave uprising he incited against the Romans…).

A WORTHY LEADER

The thing about Shohei’s emperorship is it’s not determined by blood and it isn’t built into a system of political divinity, unlike every Japanese Emperor’s until World War Two. Shohei’s value is quantifiable and tangible. A big part of his success is purely work ethic: it’s virtually impossible for most players to both hit and pitch as the amount of daily practice they’re expected to do exceeds any sane metric. Shohei lives and breathes his chosen craft, it’s legitimately inspiring and, I’d argue, inarguably exemplary. His demeanor is humble and courteous in a way few athletes’ are.

My favorite Shohei moment is when he accidentally almost hits then-Oakland A’s left fielder Mark Canha with an up and in fastball. He’s trying to do a high fast ball, only he misses slightly and it damn near grazes Canha’s face. Canha responds understandably—it scared the shit out of him—yelling, “C’mon, Sho!” slightly aggressively. Shohei’s catcher immediately gets up in Canha’s face, it’s disrespectful to yell at Shohei like that, as he well should. Shohei’s reaction is priceless. He initially squats down and bows, holding his head in his hands, in apology for almost hitting Canha in the face. Then a whole scrum happens, when Canha starts yelling back at the catcher, and it’s mayhem. The benches clear. But Shohei just stays standing there on the mound, looking around smiling—embarrassed almost. He catches the eye of the umpire, and shrugs almost like he’s apologizing. It’s so infectious, the umpire just shrugs and smiles back. All around them, grown men in tight pants act like little boys.

Waiting to check-in my dad at the airport after visiting him in Hokkaido, I notice Shohei’s on the TV again. “Shohei,” I announce. I’ve been commenting on it all trip. We sit there and watch, we’ve got time to kill.

It’s not just a regular highlight. It’s news. He and his wife have given birth to their first child: a baby girl. Shohei comes out and thanks his daughter for making him and his wife “very nervous yet anxious” parents. It’s on every TV. It’s a damn national holiday.

The question is not whether you should follow a worthy leader with honor and duty to the death, literally or symbolically. Instead, the question is: are you choosing what and who you follow, deliberately, intentionally? Are you following the right leader? Of course, an overly collectivist outlook can lead to tyranny. But an overly individualized one, that rejects all forms of patrimony, leads to chaos. Excess. Complete detachment from the forces that allowed such a lax collective view to spawn in the first place. My emperors are dead writers. Worthy mentors. I revere and follow them. I serve them, yet not blindly. I choose the right mentors and leaders.

Shohei, I’d wager, is a good, worthy leader.

Sean Thor Conroe (Sho Kamura) is a Japanese American writer.

What an enjoyable, insightful article!

Sean Thor Conroe plumbs the depths of Japanese corporate consciousness through history and literature and emerges with insight into the current phenomenon of Shohei veneration. I fully agree that true leaders prove their worth through words and actions that reveal internal integrity and character. Shohei has caught the world's attention not only because he is top of his game, but because he regularly displays counter-cultural virtues like humility and deference, that, I'd venture, are in short supply today.