Looking for Berto

A broken ballet

Programme notes

This archive-ballet takes its name, of course, from the film Looking for Langston which historically reupholsters the romantic substance of a queer Black poet in the thirties. When first looking into Pasuka about seven years ago, an online search did not dredge up all too much. Since then, his story has been in relative circulation. Still, from entry to entry one finds the same recycled details, some spurious, and it becomes frustrating trying to look between the biographical fenceposts and make out, however hazily, the thing that really interests me: the off-stage life. The life of the in-between – his ballet training in London, his social life in thirties and forties bohemian London, his touring Europe, etc. This libretto grasps for a backdrop, for scenery. Possibilities rise up and dissolve here in a series of tableaux – a feature of 19th century ballet libretti that entailed not just the static living pictures the word conjures today, but also in-motion pictorial scenes.

Overture

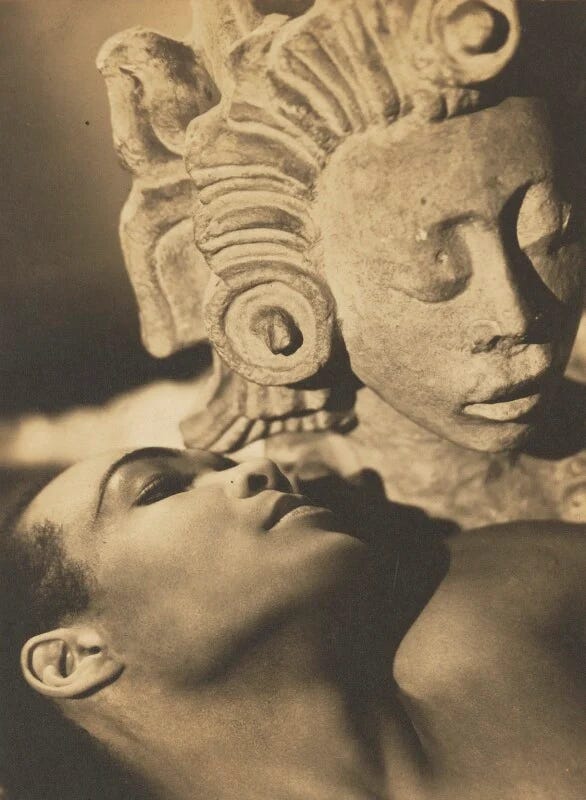

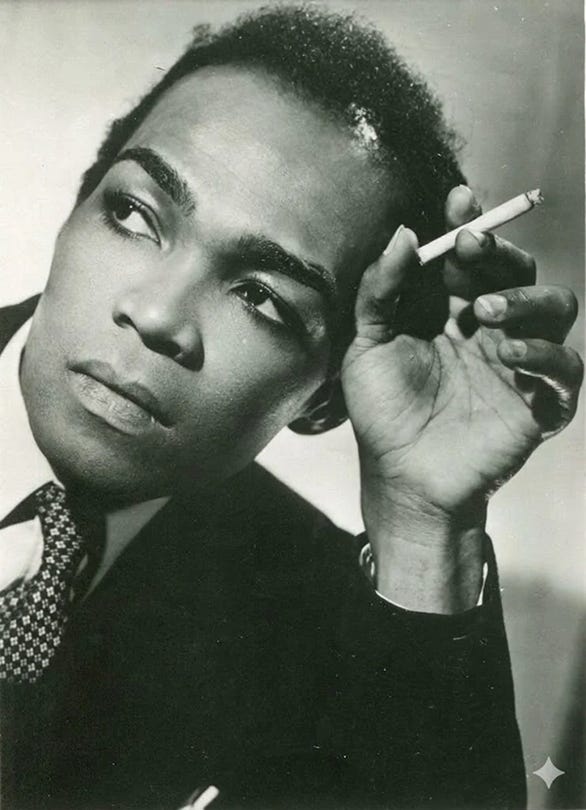

A reviewer for Stage and Screen announced in the Summer of 1947, “Berto Pasuka is the most colourful dance-personality since Isadora Duncan. Glamor-starved Europe greeted his continental tour with wild enthusiasm.” The reviewer, it seems, could not get glamour out of his head and photographs of Pasuka throughout his lifetime help elucidate. In some we see a soignée figure smoking in suits that might be expensively tailored or just dandified by Pasuka’s mere donning of them, in others the consummate maître de ballet behind the scenes. In others yet, we see him in the unearthly outsider roles he wrote for himself – a prophet set on flying to paradise, a philosopher-pianist trying to marshal living keys into harmony, a mystic priest in a blood rite. Never the romantic lead or everyman protagonist. Take note: the foundations of this Black British art were surrealist, phantasmagorical, fabulous in the traditional sense of the word—less so kitchen-sink.

Tableau

Up goes a silk backdrop of snowy mountains, painted almost like gateaux: dusted blancmange and white cream avalanches with clementine blushes at the domed or tapered peaks. In front of this, the cross-section of a train. We can see into the cabins. We see frosted pines and an icy lake through the train window as the backdrop moves along a rope. Members of Les Ballet Nègres are lounging, sleeping, writing letters, reading, playing cards, gossiping. Pink light glances through the window. We see at the other end of the train Pasuka enter the dining car alone with a notebook. He is looking for somewhere quiet to formulate a new ballet. Out the window, flakes drift. He sees a group on horseback, bronze flickers. For a moment he wonders if it is his fellow cast, this other party of Black men and women in the Alpine mountains, 1947. But these figures, cantering through the snow, are much older, and bedecked in curious adornments. They pass out of sight. An angry-looking man is coming towards him telling him breakfast is finished and to vacate the dining car...

Act 1

In Pasuka’s Market Day, which gives a day in the life of a community of vendors, a gaggle of white tourists disembark from their cruise ship and pass through an island market scene. This wasn’t unfamiliar territory for Pasuka and his dance company co-founder, Richie Riley. Their interest in classical ballet was in part born from the excitement of Marcus Garvey’s Edelweiss Amusement Park, which was set to include a dance company. Whilst that company ended, Pasuka and Riley started their own corps through performing for tourists in hotels. Frustrated by a lack of prospects however, Pasuka decided to further his training and enrol in a ballet class in London.

Tableau

A passenger ship bound for Southampton. A figure smokes in the glazed observation lounge, their back to us, watching the flat expanse of sea. The linearity of this mis-en-scene is cut suddenly by a dancer, Pasuka, practicing. From the swaying sheets of fabric representing the nearest waters, figures occasionally rise and descend; it is unclear if they have been glimpsed by Pasuka, who continues his dance. The figure in the bar gets up. Sometime later we see them outside strolling along the deck. Pasuka stops dancing.

Act 2

Pasuka arrived in London as early as 1938. Most sources report him as fine-tuning his classical training at the Astafeiva School in Chelsea. This was located at the Pheasantry on Kings Road. Students included Margot Fontyn and Anton Dolin. Founded by Tolstoy-descended princess, Serafina Astafeiva, who danced with the Ballet Russes, it was visited frequently by her mentor Sergei Diaghilev who came to scout for his company.

How did it strike Pasuka, this building, entering its caryatid-flanked triumphal arch, passing through its quadrangle to meet more caryatids amid the “flamboyant Louis XV façade” and “the odd, extremely heavy display of Grecian enthusiasm”? Or did he even attend school at this site after all? Similar sources also say Riley trained here too, but Astafieva was dead by the time either were in London. The Pheasantry still stands today, now home to a Pizza Express. On the floor of the old dance studio remain the mirrors and bars put in by Astafieva and so it is not impossible that a school continued under her name for a period. It is worth noting that such schooling was prestigious but non-institutional, much like Pasuka’s other training in England. It is unlikely he would have been admitted to train at Sadlers Wells or the Royal Ballet who only took its first Black student, Brenda Garratt-Glassman, in the ‘70s.

Tableau

Pasuka in the courtyard. He glimpses in the face of one caryatid something hidden, obscure, at odds with its Grecian style. In older pictures, the two in the internal courtyard are also black but have been painted white, a fact that might have amused Pasuka. He moves around in the quadrangle and these caryatids step down from their alcoves, sick of holding up the building, and join him in a strange silent dance. Faces appear at all the windows, peering down at Berto.

Act 3

Gemma Romaine tells us,

“George Bernard Shaw was among those who supported Les Ballets Nègres which were financed in part by Pasuka’s lover. Support for their endeavours came from the capital’s African diaspora: from London-born dancer John Lagey, who became well-known as wrestler Johnny Kwango, to wardrobe mistress Vi Thompson, the first African girl to attend Roedean and a member of the Yoruba elite.”

In Les Ballet Nègres there was to be no entrechats, no pointe work, in fact, Pasuka devised that the company was the “complete antithesis” of Ballet Russes, which was he felt an “irrelevant dance idiom” for his conception of modern Black dance forms.

They debuted in April of 1946 at the Twentieth Century Theatre in Westbourne Grove. The four ballets written and devised by Pasuka, like all the company’s repertoire, drew on folklore and Black, (specifically diaspora) stories. One called Aggrey takes its title from the name of Ghanaian-born philosopher and Pan-Africanist ‘James Emman Kwegyir Aggrey’. Another, De Prophet, based in part on real-life incidents in 1920s Jamaica, centres on a miracle healer and prophet whose promises to ascend to heaven end up with his arrest by a British officer and ensuing imprisonment.

Despite a transcontinental outpouring of critical and public support they did not win a single Arts Council bid or secure sufficient private funding. Though it was described in 1999, forty decades after its closure, as “the ballet that went to sleep” (invoking Richie Riley’s own words), its influence has been recognised as foundational to Black dance in Britain, but it is less credited for shaping the very contours of modern dance in Europe.

Riley says of Pasuka in the documentary Black Ballet, “... if he felt the audience with him, you knew the ballet would go on.” The audience, the critics, even amid all the racism and bafflement at avant garde Black dance, were with him. It was not lack of ticket sales but ultimately bureaucratic parochialism that led to the closure of Les Ballet Nègres.

The ballet disbanded in 1952 with its members dispersing into other companies or careers entirely. Pasuka relocated to Paris and also retrained as an artist (exhibiting a solo show at the Grand Palais as well as in London) and working as an artist model. However, he did continue to dance, returning to London for the Royal Court Theatre in 1959. Various sources mention Pasuka’s “mysterious” death in 1963, namely that he was found in his apartment in Paris and transported to Wimbledon hospital in London where he died. Some accounts mention sickness, others allude to a violent incident with his lover…

Apotheosis

‘Apotheosis’, traditionally used at the end of ballet libretti, also describes a divine state, often depicted by showing the assumption of saints into heaven, much like Pasuka’s own character disastrously sought. This tableau-finale takes place in the infamous Café Royal. Known as a bohemian “labour exchange” for artists’ models, it is also identified as a site around which Black queer people constellated at the time: socialising, romancing, securing work (or not) beneath its peeling gilt stucco and tarnished gold scrollwork ceilings.

Tableau

It is here we witness Pasuka and his company in a crowd; it is unclear if they are dancing or naturally weaving through the overcrowded café in a semi-rhythmic sway. Things become half-lit and subtly tinted, at other times flickering into bright, almost unbearable, corporeality. Pasuka disappears into the throng, around whom flutter the scattered pages of a lost ballet, afro-orphic fragments in a gilded café.

Image Sources: 1. Photo from the National Portrait Gallery, Photographs Collection 2. Making Queer History 3. From the Smith Archive (Alamy) 4. Photo from the National Portrait Gallery, Photographs Collection

Shola von Reinhold is a writer and artist from Scotland.