My Own Subjective Measure

How subjective time makes me question objective reality.

I like to listen to podcasts at the gym.

I walk in, take a sip of water at the fountain, and then make my way to the elliptical for a warmup at resistance seven. I always use the same machine — one that gives me a view of everything.

On the far right near the entrance is the deadlift station. Testosterone levels are high over there. Muscley dudes take turns pacing in circles between sets. The amount they sweat surprises me considering the exercise doesn’t entail much movement. Then again, I know nothing about deadlifting. I’m always impressed by the singular powerful femme who keeps a spot in the rotation. Her movements are sharp and tight. She makes eye contact with herself in the mirror and no one else. She seems intense; I imagine her as a lesbian in tech.

Then, there’s the free weight section in front of me, around which there’s always a group of four or five guys of varying sizes who all know each other. They take turns doing bench presses, but mostly they stand around and make jokes. I wonder about their pack dynamic, and what it would feel like to be part of it.

How exhilarating it is around 6:30pm when every treadmill is occupied. Everyone’s feet pound on the swooshing rubber in a rhythm that makes me feel like we’re all really going somewhere. Except maybe — the girl on the stair master. Is she bored? She looks bored, or maybe just unimpressed. She wears a perfect, slicked back pony tail, matching spandex bra and leggings, and over-ear headphones. She never sweats, and she climbs the machine for what seems like an eternity… Each step just as blasé as the last.

Then finally, the maze of weight machines to my left that lead to the mats—the deepest alcove in the gym where I spend the majority of my time.

Today, I’m listening to an interview with Harvard scientist, Dr. Ellen Langer. She describes a study she conducted about the body-mind connection.

To start, they put people in a room by themselves with a computer and a clock. Then, they inflict a wound. It’s a minor wound, she says — no one was stabbed — but with this minor wound, participants are asked to sit and play computer games with the instruction to switch games every fifteen minutes. They can use the clock on the wall to keep track of time. Unbeknownst to them, the clock is rigged.

For a third of the people, the clock ticks twice as fast as real time. For a third of the people, the clock ticks half as fast as real time. And for the final third, the clock is “real” time.

After the experiment, she and her team run a series of tests, and the results show that the wounds heal at the rate of perceived time. As in, for those who are in a room with a clock ticking twice as fast as “real” time, their bodies respond by creating the necessary proteins, blood vessels, and skin cells at a faster rate than those in a room with a clock ticking at the pace of “real” time.

What the fuck?

I can’t believe what I’m hearing. I increase my resistance to ten. I push hard against the machine and it feels good. I feel liberated by this information, intoxicated even. I have a pretty gnarly burn on my hand. I look at it. I imagine the skin cells gathering around my wound’s edge, then migrating and multiplying inwards, forming themselves anew. I imagine my skin proliferating along the surface of me at my own subjective measure of time…

My own subjective measure. How trans.

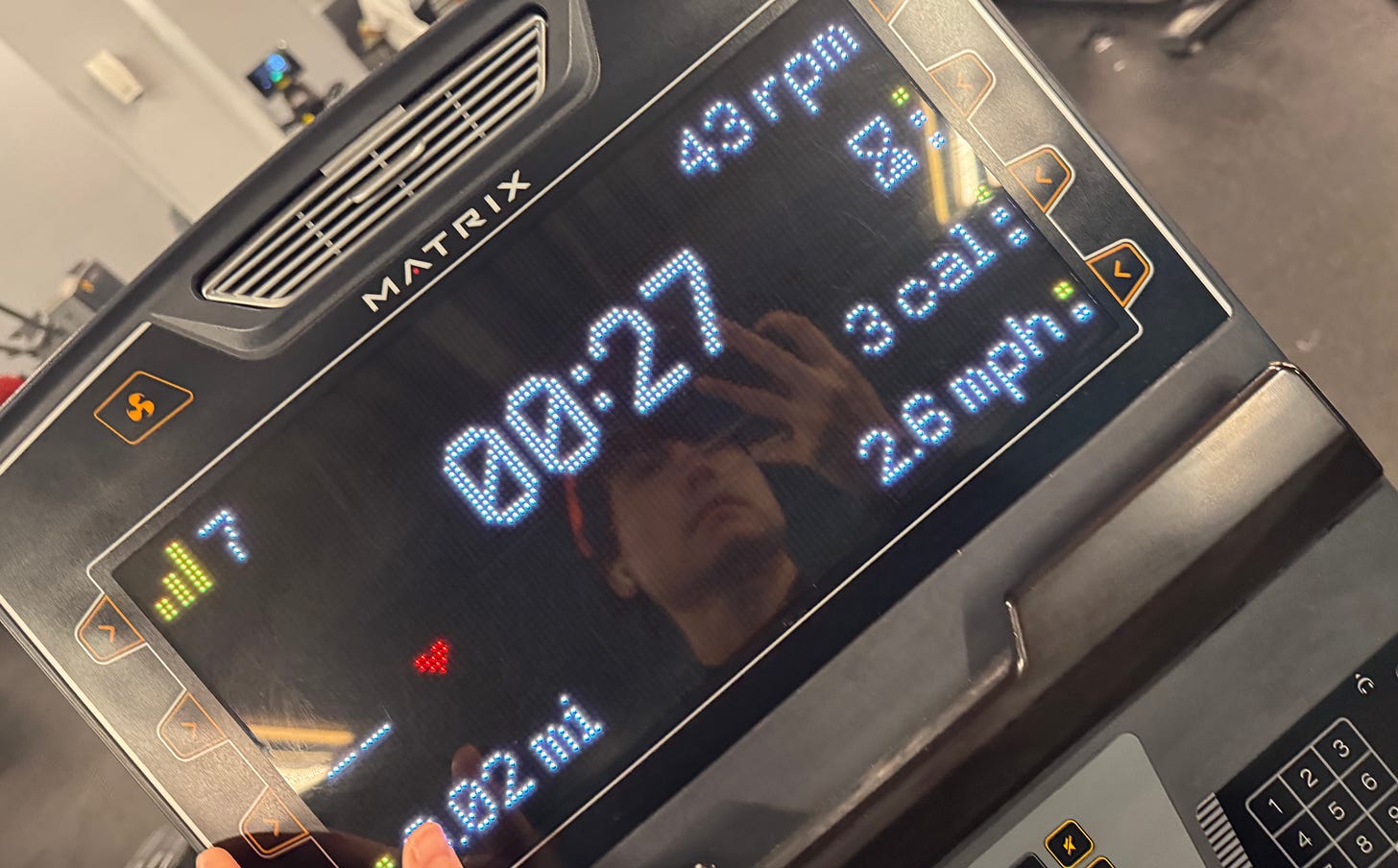

I land back in the present and realize I’ve been on the elliptical for twenty minutes, longer than my usual twelve — just enough time to break a sweat. I get off, wipe the machine down, and head to the mats. Dr. Langer has moved on to a study about Alzheimer’s, but my mind is still on rigged clocks.

I pause the interview and switch to a Bearcat DJ set while I stretch.

People often use the word “warped” when describing a subjective experience of time. Time warps in moments of crisis by slowing down. It speeds up when we’re dining with old friends. It falls away completely as we discover a new love. But the idea that “perceived time” or “subjective time” can have a measurable impact on automatic processes our bodies perform suggests that all time is warped. There is no “objective” time.

As a trans person, my orientation towards “objectivity” is already a bit… limber. On testosterone, I am constantly amazed at how a liquid hormone I inject once a week can have such a dramatic impact on what I thought were the “solid” structures of my body. In the past year, I have watched the bones in my face shift, my shoulders broaden, and my hips become more narrow somehow. It feels like my skeleton is reassembling itself in preparation for flight.

And this new body of mine soars. I swing my arms in front of me with a twenty-pound kettle bell, and I feel more alive than ever. When I was first transitioning, I felt my true gender to be that of a middle school boy. In retrospect, it makes sense. I wanted to begin my gender journey from the time at which it starts to matter: puberty. My transition allowed me to embody my own kind of adolescence, an experience I feel I missed out on the first time. Maybe this is why trans people are often perceived as much younger than they are. Many of us have had to reconstruct our past to retrieve ourselves, and in the process, we warp time.

Bearcat introduces a beat I recognize, and when the chorus drops, I am transported to the dance floor.

I’m at Honcho, a queer camping festival in Pennsylvania. I’m close to the DJ booth by the speakers. I let a Doll go in front of me and scream, “Yes, girl! That’s where you belong!” in a euphoric haze.

My body pumps to the music, “Pussy, pussy, pussy, wussy, pussy state of mind.” The crowd chants, “Pussy state of mind! Pussy state of mind!”

Yes, exactly, I think. It’s all a state of mind.

The Dolls scream the loudest. If only everyone knew…

I watch my biceps bulge in the mirror as I lift fifteen-pound dumbbells in time with the beat. I always feel super manly when I do bicep curls. Our bodies respond to what we believe is true, if only everyone knew. My mind swirls around the relationship between subjective/objective time and the subjective/objective body. I can’t make complete sense of it. I look to my left and see an elderly man using the “chest fly machine.” He wears jeans and work boots, and reminds me of my uncle. I avert my eyes out of courtesy and am transported again.

I’m twelve and my mom and I are taking the 6 train up to the Bronx to check on my uncle. We find him, as we often do, sitting on a milk crate in front of a Bodega. He flexes his biceps and curls his forearm up and down as if he’s lifting a weight, but his hands are empty.

“You don’t need no weights, just lift them in your mind, and you get muscle,” he says to me.

I finish my set and drop the dumbbells on the ground. I catch my breath. Does gender start in the mind or in the body? Another swirling, shimmering question. I look around as I pace, just like the guys who deadlift.

Everyone here is exercising to support their objective health, of course, but also as a way to maintain or modify a subjective presentation of their body that affirms who they want to be in the world. The dance between objective action and subjective effect/subjective action and objective effect makes my brain vibrate in a way that’s pleasurable. It makes me feel more connected to everyone here. The mat area is flanked by two walls that face each other with floor to ceiling mirrors, creating an infinity effect. In each reflected reality, I can feel people becoming themselves over and over…

I look back at my own reflection – my arms are swollen from lifting and I like how big they look. My t-shirt is tight enough that you can see the outline of my pec muscles and my sweat soaking through increases the effect. Like all the boys in gym class growing up, I lift my shirt and use it to wipe my face, not caring how much of me is seen.