Reps without rhyme or reason

Notes on soccer, unrequited love, repetition, and change

I would barely consider myself superstitious… not even a “little stitious”. In some ways, I think I recoil at the idea of superstitions, as it makes my pessimism squirm at the notion that some set of repeated motions done (or avoided) perfectly might have the capacity to externally affect something. On top of that, I am a bit careless, often wearing mix-and-match socks, and, to the chagrin of many people in my life, splitting the poll is sometimes more efficient. That said, what I am about to disclose might seem contradictory, but I assure you it is not a conjuring or an expectant ritual—it was and is simply an amassing of repeated gestures done with little regard to what would follow.

Step I: Begin with your chest bent over your knees, peering down at your shins and feet. Do so lovingly and with admiration.

Step II: Delicately loosen and then slip off your sneakers.

Step III: Bring shoeless, soccer socked feet side by side, arch to arch, to the point where your calf muscles touch at their widest point à la late Middle Kingdom Pharaoh.

Step IV: Draw out your cleats from your bag, set them to the right of your legs, mirroring the stance of your feet.

Step V: Set your cleats, one at a time, beneath a raised leg, push, and then wriggle your foot into them. First the left, then the right.

Step VI: Pull fingers through each of the laced x’s on the cleats and tighten them. Eventually, bring the tips of the laces evenly to their full height. Tie them, double-knot.

Step VII: Place hands on knees to brace as you gaze down at your work.

Repeat before every practice and game.

For almost two decades of my life, I played soccer, starting from 4v4 chaos on Pugg goals, to Division 1 Collegiate Soccer. Of course, there are flashes of beautiful moments of play that I think back to, such as streaking down the left flank, banging in a cross after having embarrassed a slowpoke rightback, or making a humbling tackle to deny some overly ambitious forward a victorious run towards goal. Yet, what comes to mind when I think about my 18 years of playing is the pregame dressing sequence, done with zero pregame fantasies, but just a deep commitment to the movements themselves.

Joan Jonas, a pioneer in video performance art, recorded herself saying “good night” and “good morning” before going to sleep and after waking every day over three different periods of her life. I once asked Joan what repetition meant to her art practice, and she offered, “At the end of the day, repetition changes you”. My skepticism aside, I cannot deny the truth in Joan’s words. Even now, as I reminisce, I can feel the muscles in my back stretch downward to my shins, my fingers tinker through my laces, and my hands rest on my knees as I admire my game-ready extremities. This is not the superstitious change in the wind I like to doubt, but an embodied shift produced through the steady practice of continually tending. Week after week, and then day after day, without any attachment to the implications of my getting-ready performance on my actual game, I repeated these same gestures deliberately and delicately. This time never felt preparatory or ritualistic; it was something deeply meaningful, bound to the moment it was in. Joan is right, repetition changes you; the seemingly mundane incantation of “good night” and “good morning” or the unlacing of a shoe done fastidiously, shifts the constellations of what holds meaning and what holds anticipation. Each step of my getting-ready practice was no longer a buildup, instead, it became a small presence-ing arrival existing in excess of, and outside of, the game.

In all honesty, my soccer heydays occurred between the ages of 6 and 11. The years that followed were met with “tests from coaches” (read grown men penalizing 13 year old girls to see how much they “want it”), concussions, bench warming, sprains, and ultimately an aptly named injury called a “Jones Fracture” that would require surgery and my brother’s tender counsel to a teary eyed 21 year old me on the phone, stating, “You know Kenny, you can’t always love things that don’t love you back”.

Soccer never really loved me back. For as long as I can remember, I endured heckling from white parents from South Georgia to New Jersey who accused me of “attacking” their daughters, who were twice my size. The injuries also accrued along with the medical gaslighting. When I was healthy, coaches would continue to overlook me for other, let’s say, fairer and less talented players, a decision often blatant enough for my parents to have to continually endure disingenuous sideline chat where other parents foolishly or spitefully asked, “Why don’t you think Kennedy is playing?” One would think it would’ve clicked for me, that this game didn’t love me back. In some ways, this unrequited love affair was very apparent; in other ways, it was a delusion that kept me going, and, in even more ways, I think my devotion to this getting-ready practice accumulated and shifted my relationship to the entire game itself. Repetition after repetition, these gestures took on meaning through their sheer unaccounted-for volume, of which ninety minutes of warming up on the sideline, never to be subbed in, could not counteract.

There is no shock that threads of racial basis and prejudice that shape every aspect of this world we live in are woven into the tapestry of women’s soccer. This is true, but what I am writing here is not an underdog's tale, or “going high when they go low”, but rather an account of something beyond it. I'm here recalling my calves, my feet, and my cleats, for whom I bent forward to tend to, day after day. This practice falls out of my year-end records, coaches' feedback, and fitness tests, yet the continual motion of it transformed my relationship to soccer indelibly. Transformed my relationship to my feet, my body, my being together—indelibly.

For 18 years, soccer dominated my life. Even now, the smell of fresh-cut grass and a very particular morning sunlight dislodges my notion of the Julian calendar and replaces it with the schedule for preseason two-day practices. Yet still, the presiding memory is not this, but rather the repeating act of taking off my sneakers and putting on my cleats, without any regard for what would follow.

In a lecture, cultural theorist Stuart Hall once said, “…the one thing that they will not look at so carefully are the contradictions which every system always produces — the things that it cannot cohere within its system of power. The thing that's always left out, that remains emergent, or remains residual. The thing that's going to knock on the door of this particular system, and say, you've left us out. How about us?” I am reminded of Hall’s notes on systems of power, not to issue a call to arms for women’s soccer, though Borges might have some thoughts on that, but to draw upon Hall’s urging to tend to these elements that are residual, irreconcilable, exceed, and accumulate outside of these systems of power. Week after week, and at some point day after day, I showed up not to the system that was dominating me but to that which it could not hold, that which it could not be carded out or benched. This silly emergent practice could not be thwarted by the metrics of the game that would follow. The repetition didn’t change my relationship to the game, but, as Joan noted, it changed me and it allowed me to endure.

I rarely play soccer now, so this practice is mainly a memory, but I hold it closely as a model, as I think about what it takes to exist and remain in a world that does not love you back, or wake up in a death-dealing system that refuses to recognize your humanity. I think about how one must still repeatedly show up, not to the system but to that which it cannot hold. That life the system cannot extinguish, that existence it cannot legislate out, that memory it cannot erase, that land it cannot wholly occupy, and that seemingly meaningless practice it cannot co-opt.

Week after week, and day after day. I assure you, this is not a conjuring spell or an expectant ritual – it is just an amassing of repeated gestures done with little regard for what will follow, trusting only that repetition will change you, and ultimately, the practice will accumulate and be accounted for.

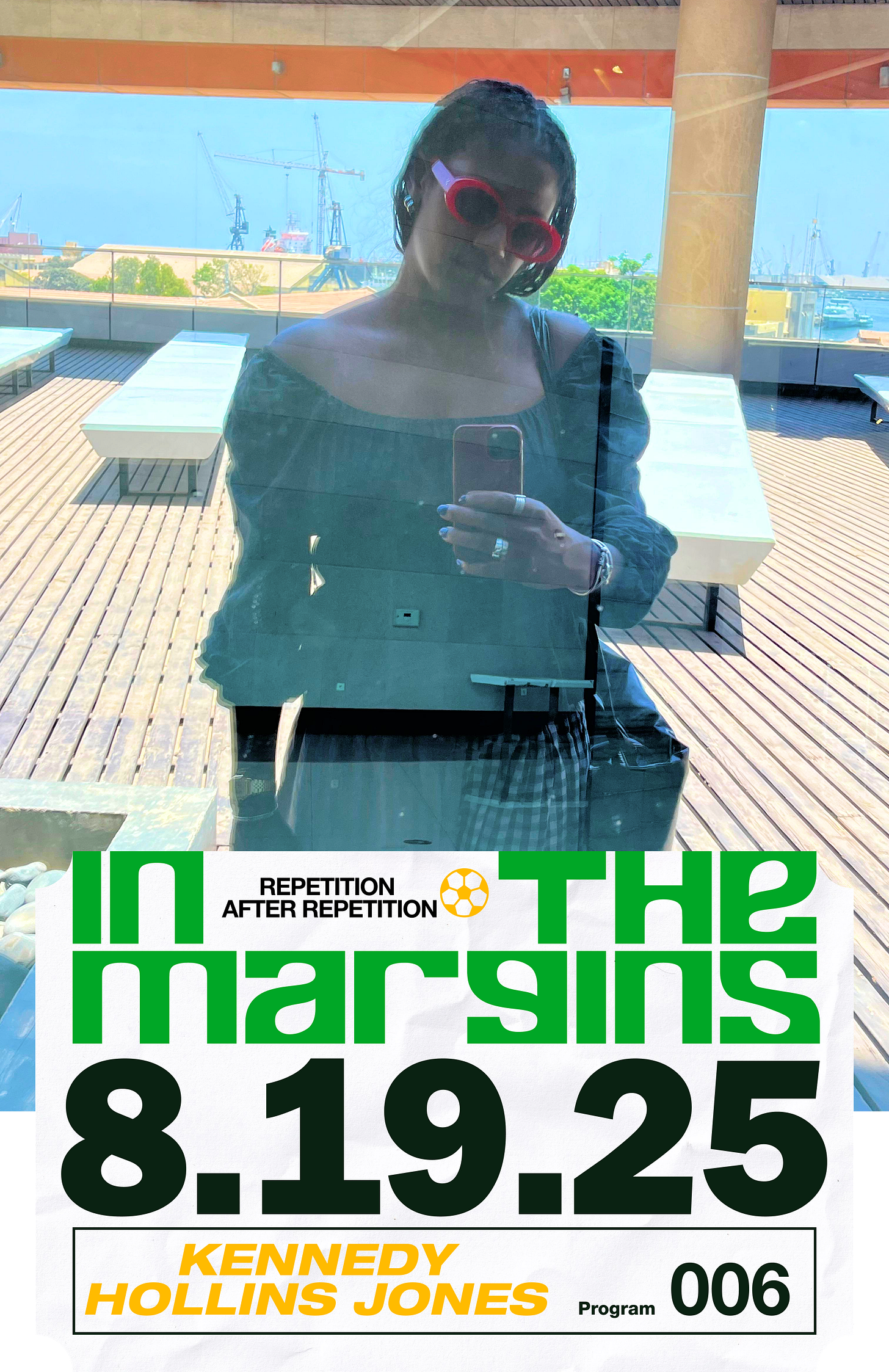

Kennedy Jones is a curator, writer, and researcher based in Brooklyn, NY.

Beautiful text!!! Please write more and let’s ball soon <3