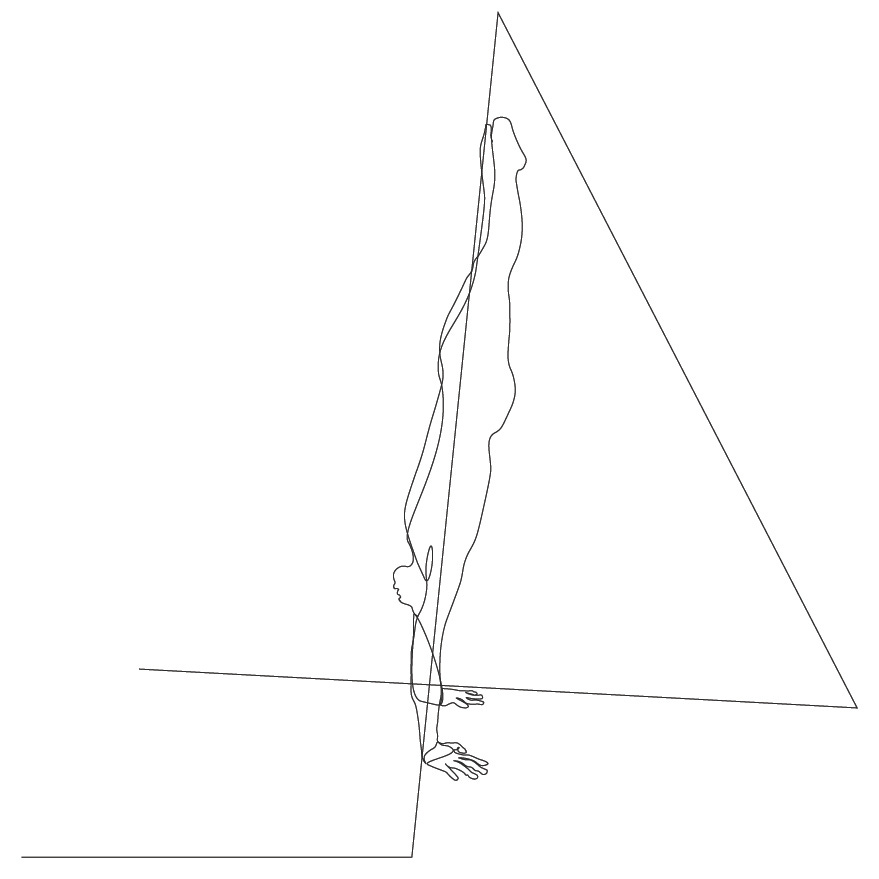

The Upside Down

On handstands and staying still

I have been handstanding some 35 years or more yet I realize I have never, not once, balanced upside down longer than I can naturally hold my breath. I don’t remember when I first turned myself upside down, but I’ve been told I was practically a baby, no more than three or four years old. I still go to the gym—and when I say “gym,” I mean a place where I do actual gymnastics, like flips and swings and turns—several times a week. I rarely try to stop and balance on my hands for more than a few seconds, but when I do make an attempt, this is what I do. It is what I’ve always done:

I inhale. I put my right foot in front of my left, I launch my lower body into the air and bring my thighs together to touch, I aim my toes toward to the sky, unshrugging my shoulders, pressing through my fingertips, stretching up, up, up…until I step back to the ground with a little puff, an almost inaudible sigh. I exhale.

I was a few weeks into a multi-month stint in Paris for work when I realized, after another long, aimless walk followed by another cold apartment dinner, that it had been the same number of weeks since I had touched another person or another person had touched me. Some moments of scrolling on ClassPass (a group fitness class aggregator) led me to a category I had never seen: l’équilibre, or “balance.” I was intrigued. Could this be a single, simple solution to my many problems: my loneliness, my skin hunger, my tendency to fall out of handstands in five or six seconds even on a good day (but had I ever really tried to have a better day?) How hard could it be?

I signed up, first for one session, then for more and more—as many as three in a week. I take “inversion” classes with yogis; and “straight legs and pointed toes” classes with circus practitioners; and “shoulder and core” classes with calisthenics enthusiasts; and “anything it takes to get the job done” classes with Crossfitters. I laugh at memes about the quest for a one-armed handstand and read issues of The Handstand Press, a magazine about handstand practice (sample quotation: “Sometimes when you feel like you are falling apart, you are actually falling into place.”).

Watching a professional hand balancer kick smoothly into position, then resting upside down as lightly as if they were sitting on the couch, you’d think: no problem. Standing, after all, is easy to take for granted. And yet to stand in one place for a duration is quite difficult—ask anyone who has worked retail. It burns in places you would never expect: the front of your shins, the bones of the palms of your feet, the small of your back. Many of us never waste time thinking about how our toes spread across the ground to allow us to balance or the angle with which our feet and our shins form “ankles” so that we remain upright. But to handstand is to think about every single one of these, and so much more. The hardworking few may make it look simple, but finding balance—true balance—is surpassingly difficult. And perhaps this was my first lesson. Handstanding turns everyone into philosophers, myself included.

I practice at home between sessions, bringing an aggressively contemplative energy to my internal observations. I consider the angle of my hips, the way my ribs rest in relation to my shoulders, the position of my head, the cadence of my breath, and above all, the weirdness of my wrists. Wrists! The longer I stare at them, the more alienated I feel. What is this thing, this nothing, this liminal place between my fingers and my arm? What is this word “wrist,” mostly consonants, surprisingly silky on the tongue? I learn that it comes from a word that means “turn.” I look at mine, rotate them, think about how passive they feel, how thin and weak they seem, skinny as skin. I practice handstands with my belly to the wall to build endurance at home on my off days. I have nothing to look at except down at this joint, this place where everything meets. How uncomfortable it is, to realize I am resting the weight of my whole body on the in between. Blood rushing to my head, I think I am the upside down. I think I am a stranger thing. When I stand, I am alarmed to feel my hands dangle, useless and limp. My flesh looks stringy and hard, with weird lumps and bulges I don’t remember being there before. There is inflammation, I know because I can hear and feel a little click when I move into position. I don’t worry. In class I’ve met a man who knows a pressure point that you can squeeze to make the pain disappear…

In the quiet of the yoga studio, the Crossfit box, the fitness salle, we often work in pairs. My French is not great, but I quickly learn that hand balancers share a vocabulary that transcends any language barrier. The word “banana,” for example. Everyone knows what that means, when your back is arched to form the shape of a curve—an easy posture for a second or two of balance, but near impossible for longer-term stability. Beyond its physiological limitations, there are aesthetic considerations: the banana handstand is ugly, and hand balancers care about nothing if not beauty. On Instagram, I follow slender athletes with flat asses and wonder how much easier the handstand is for them than for me: a grown woman with a grown woman’s body. I know I will always be an s-curve, never again a ruler. I wonder if that means I will never be able to hold a handstand. I know I am looking for excuses.

How do I know they’re merely excuses? I know because I am coached. For the first time, I have guides whose entire vocation is handstands—not flipping, not twirling, no bars or beam or vaulting, just handstands. My favorite, I think he’s Italian, watches intently and then imitates me as he explains: arms overhead. A giant gulp of air. Proud chest, ribs flaring, back rigid. A gesture of exploding, disintegrating. You must learn to breathe into your side body, into the back of your ribs, into the small of your back, he tells me. I blink. The click of a new paradigm shifting into place is palpable, almost audible. I had never before imagined that handstands and breathing could be connected, not in any way, not once. After a moment’s pause, I kick up again.

I hesitate at first to document my work, but realize there really is no other way to prove that I can hold it for ten seconds sometimes, or to see exactly why my second leg always knocks my first out of alignment. From images, I learn that in a handstand all the blood in my body drips to my head—not my face, but the tip of my skull, like yolk sliding to the top of an egg. My skin, my cheeks, my lips and neck all sag upward—in other words, downward—toward my hairline. Instead of looking like a healthier, stronger version of myself, I look constipated, sick, terrified, tortured. Maybe the picture-perfect handstand is reserved for the young.

I say this, even as I observe that hand balancing is an age-agnostic activity. My social media feeds—and I have one feed focused particularly on handstands—are filled with children, young adults, circus athletes, yoga fanatics, and also older adults. To become interested in handstanding is to turn your attention to what it means to stay still. To get better at handstands, as I have been very slowly getting better, is to be able to stay still for longer and longer. There are balancers in their teens and balancers in their sixties who are far better than I ever have been because they know something that I desperately want to know, something I am slowly learning, something about what it means to pause, to concentrate, to focus, to rest.

I have never been good at rest, however now I have found a direct line; I am injecting its pleasures straight into my throbbing veins, I am drinking it in. I once read in the Handstand Press that perhaps the handstand is simply “a suspended moment out of reality and its weight. Floating in stillness.” In the handstand position, I can focus only on staying up. My roaming thoughts, always so intrusive, fade. My mind scans my body from the tips of my toes to the base of my palms, again and again; there is room for nothing else. Blood has filled my head, heat has filled my brain, even my back space is full of breath. I am floating. I am connected to my core, I am connected to my foundations. My hands are my foundations. I am upside down. I am up. I am, finally, staying up.

Steffani Jemison is an artist and writer in Brooklyn, NY.